ТЕКСТ АННА ШЕВЧЕНКО

ДЛЯ THE ART NEWSPAPER RUSSIAtext anna shevchenko

for THE ART NEWSPAPER RUSSIA

молодость

биенналеAn Indian

Summer for

the Biennale

Архитектурная биеннале в Венеции, несмотря на относительную юность, самая престижная в мире выставка архитектуры. Выделившись из Венецианской биеннале современного искусства лишь в 1980 году, выставка возникла как экспериментальное пространство для архитектурного сообщества и со временем завоевала огромную популярность. Этому способствовал и принцип сменяемости кураторов, чьи взгляды зачастую диаметрально противоположны: радикалы сменяются миротворцами, визионеры — реалистами, а теоретики — практиками.

Despite its relative youth, the Architectural Biennale in Venice is the most prestigious exhibition of its kind worldwide. Only emerging as distinct from the Venice Biennale for Contemporary Art as recently as 1980, the exhibition was intended as an experimental space for the architectural community and has grown in popularity over time. This has been facilitated by the principle of constantly changing curators, often of diametrically opposed opinions: radicals alternating with conciliators, visionaries with realists, and theoreticians with their more practical counterparts.

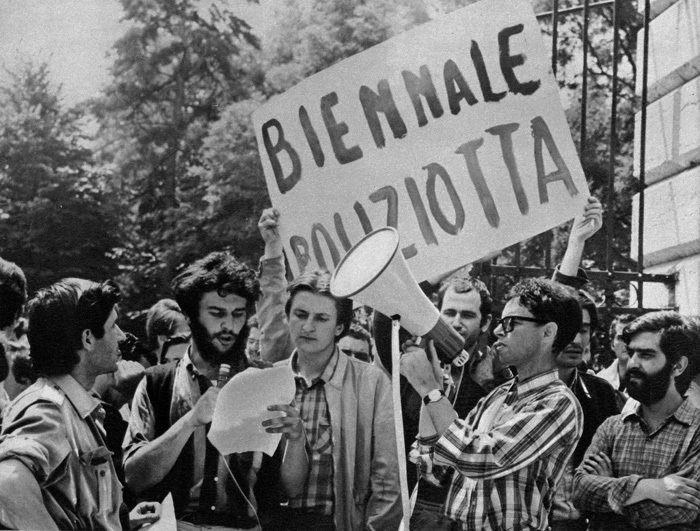

История биеннале отражает смену архитектурных дискурсов последних 35 лет. Возникновению выставки как отдельного события предшествовали протесты студентов и присоединившиеся к ним художников 1968 года. Повернуть институцию лицом к народу был призван архитектор Витторио Греготти, назначенный в 1974 году ее руководителем. Греготти настоял на включении в биеннале небольшой архитектурной экспозиции. Эта и другие его выставки заложили основу для дальнейшей эмансипации архитектурного сегмента.

Первая Международная архитектурная биеннале в Венеции состоялась в 1980 году под руководством архитектора и историка Паоло Портогези. Выставка проходила под девизом Присутствие прошлого. Портогези соорудил декорацию в виде «постмодернистской улицы», составленной из фасадов авторства 20 приглашенных архитекторов. Витторио Греготти назвал экспозицию «оргией фальшивых колонн», а Рем Колхас посмеялся над этой потемкинской деревней, представив фасад из белой занавески, резко контрастировавший с богато декорированными соседями.

В 1985–1986 годах биеннале руководил Альдо Росси, влиятельный итальянский архитектор и теоретик. За два года он умудрился провести две довольно камерные выставки, причем один раз в формате конкурса. Следующая прошла в 1991 году. Историк Франческо Даль Ко взял за образец арт-биеннале и впервые включил в работу национальные павильоны, которые до этого простаивали в садах Джардини. Ханс Холляйн — первый неитальянец среди кураторов — в 1996 году предложил порассуждать о «способности архитектора улавливать подземные вибрации настоящего и транслировать их в будущее», для чего пригласил 70 архитекторов выставить свои главные проекты.

The history of the Biennale reflects the shifts that have taken place in architectural discourse over the last thirty-five years. The appearance of the exhibition as a separate event had been preceded by the 1968 student protests, joined by various artists. Turning the face of the institution to the people had been urged by the architect Vittorio Gregotti, who was appointed curator in 1974. Gregotti insisted on the inclusion of a small architectural exposition in the Biennale. Along with his other exhibitions, this laid the foundations for the subsequent emancipation of the architectural segment.

The first International Architectural Biennale in Venice took place in 1980 under the supervision of the architect and historian Paolo Portoghesi. It was held under the motto “Presence of the Past”. Portoghesi ordered the creation of a “postmodernist street” made up of facades produced by twenty guest architects. Vittorio Gregotti termed this exposition an “orgy of false columns”, while Rem Koolhaas mocked it as a Potemkin village, contributing a facade of white curtains, sharply contrasting with its richly adorned neighbours.

In 1985-1986, the Biennale was run by Aldo Rossi, an influential Italian architect and theoretician. In these two years, he managed to put on two quite low-key exhibitions, one in competition format. The next exhibition would take place in 1991. The historian Francesco Dal Co took the Art Biennale as his model and was the first to involve the national pavilions, which had previously been left standing idle in the Giardini. Hans Hollein – the first non-Italian curator – proposed in 1996 that thought be given to “the ability of the architect to capture the underground vibrations of the present and translate them into the future”, for which he invited seventy architects to display their chief projects.

«Меньше эстетики, больше этики»,

куратор Массимилиано Фуксас,

2000«Less Aesthetics, More Ethics»,

curator Massimiliano Fuksas,

2000

Проект куратора выставки 2000 года итальянского архитектора Массимилиано Фуксаса стал переломным для биеннале. Его фраза «меньше эстетики, больше этики» и сейчас звучит актуально, поскольку положила начало идущей уже 15 лет дискуссии о социальных аспектах работы архитектора. Революционный подход Фуксаса (который, кстати, принимал участие в тех самых протестах 1968 года) заключался в отказе от рассмотрения архитектуры как отдельных зданий и фокусировался на проблемах городов в контексте ускоренной урбанизации. Фуксас поставил задачу «использовать биеннале в качестве лаборатории, анализирующей новое планетарное измерение городских трансформаций». Это выражалось и в смене подхода к экспозиции: переосмыслив «улицу» Портогези, куратор установил 300-метровый экран, транслировавший жизнь «мегалополисов» — Боготы, Буэнос-Айреса, Парижа и других. Вдобавок он сумел захватить гораздо больше выставочного пространства, чем кто-либо до него.

A project by the curator of the 2000 exhibition, the Italian architect Massimiliano Fuksas, came to be a turning point for the Biennale. His catchphrase “Less Aesthetics, More Ethics” sounds pertinent even now, in so far as it served as the impulse for a discussion now underway for fifteen years on the social aspects of the architectural calling. Fuksas’ revolutionary approach (he had, incidentally, taken a direct part in the protests of 1968) consisted of a rejection of the concept of architecture as that of separate buildings, focussing instead on the problems of cities in the context of accelerating urbanisation. Fuksas assigned the task of “using the Biennale as a laboratory to analyse the new global dimensions of urban transformations”. This found expression in a change of approach to exposition practice: having subjected the “street” of Portoghesi to review, the curator set up a 300-metre screen, broadcasting the lives of such “megalopolises” as Bogota, Buenos Aires, Paris and others. In addition, he managed to secure a far larger exhibition space than any of his predecessors.

«Метаморфозы»,

куратор Курт Форстер,

2004«Metamorph»,

CURATOR Kurt Forster,

2004

К 2002 году выставка наконец стала проходить каждые два года. Критик Деян Суджич вернулся от концептуального к материальному, сфокусировавшись исключительно на реальных стройках и предсказав перенос архитектурной деятельности в Китай. Тем временем набирало обороты компьютерное моделирование, и биеннале Метаморфозы 2004 года историка Курта Форстера отразила этот тренд. Выставку заполонили макеты всевозможных «блобов», криволинейных оболочек и гибридных ландшафтов, предвестников современной параметрической архитектуры. В 2006-м тема биеннале опять меняет масштаб: профессор Лондонской школы экономики Ричард Бердетт призывает к критическому осмыслению всего и вся, снова подняв вопрос о роли архитектора в создании городского ландшафта. Экспозиция, посвященная крупным городам и их проблемам, продолжает линию Фуксаса, но теперь ориентирована не на атмосферность, а на карты, трехмерные графики и данные статистики.

By 2002, the exhibition had finally settled down to a regular biennial calendar. The critic Deyan Sudjic heralded a return from the conceptual to the material, concentrating exclusively on real buildings and predicting a transferal of architectural activity to China. At the same time, breakthroughs were occurring in computer modelling, and the 2004 “Metamorph” Biennale of the historian Kurt Forster reflected this trend. The exhibition was filled with models of all manner of “blobs”, irregularly contoured envelopes and hybrid landscapes, the predecessors of contemporary parametric architecture. In 2006, the theme of the Biennale once more underwent a change in scale: London School of Economics professor Richard Burdett urged a critical rethinking of all and everything, raising once again the question of the role of the architect in the creation of the urban landscape. His exposition, dedicated to major cities and their problems, continued Fuksas’ line, though now oriented on maps, 3D graphics and statistics rather than atmospherics.

«Архитектура за пределами зданий»,

куратор Аарон Бетски,

2008«Out There: Architecture Beyond Building»,

CURATOR Aaron Betsky,

2008

В противовес такому строгому реализму архитектурный критик Аарон Бетски в 2008 году пытается заглянуть за пределы построек (Out There: Architecture Beyond Building). Он заявил, что здания превратились в могилу архитектуры, и включил в экспозицию элементы кино, современного искусства, дизайна и перформанса. Получилось настолько зрелищно, что выставка даже подверглась критике за чрезмерное сходство с биеннале современного искусства. Впрочем, далее последовали не менее визуально-ориентированные Люди встречаются в архитектуре Кадзуё Сэдзимы (2010) и Common Ground Дэвида Чипперфилда (2012), по-разному балансировавшие между эстетикой и этикой архитектуры.

As a counter weight to such severe realism, the architectural critic Aaron Betsky tried, in 2008, to look beyond the bounds of building (“Out There: Architecture Beyond Building”). He declared that buildings had transformed into the tomb of architecture, and included elements of cinema, contemporary art, design and performance in the exposition. The result was so spectacular that the exhibition even came under criticism for encroaching too far into the territory of the Contemporary Art Biennale. Nevertheless, this was followed by the no less visually oriented “People Meet in Architecture” by Kazuyo Sejima (2010) and David Chipperfield’s “Common Ground” (2012), each in their own way finding a balance between the aesthetics and ethics of architecture.

«Основы»,

куратор Рем Колхас,

2014«Fundamentals»,

CURATOR Rem Koolhaas,

2014

Следующим важным этапом истории биеннале стало согласие Рема Колхаса выступить в роли куратора выставки. Он решил обратиться к основам (Fundamentals) и заодно избавиться от звезд архитектуры, долгие годы не покидавших площадок биеннале. Поэтому в 2014-м «стархитекторов» заменили базовые элементы архитектуры: пол, стены, крыша, двери, туалеты, исследованные вдоль и поперек студентами Гарварда. «Сейчас, в эпоху цифровых технологий, главный риск в том, что архитектура не способна осмыслить свой собственный арсенал», — предупреждает Колхас. Впрочем, не ясно, каким образом всепоглощающий поток информации мог способствовать осмыслению, — все находки так и остались на уровне интеллектуальной эквилибристики. Национальные павильоны, прилежно изучившие собственное наследие модернизма, тоже остались при своих. Зато выставка продлилась шесть месяцев вместо трех.

За почти четыре десятилетия биеннале прошла путь от полунеформальной площадки до крупнейшего агрегатора архитектурного истеблишмента. Выбор Алехандро Аравены главой предстоящей XV Архитектурной биеннале знаменует очередной поворот к вопросам этики. Аравена, пожалуй, наиболее социально ориентированный куратор в истории биеннале и один из ярчайших представителей нового поколения. Удастся ли ему вдохнуть новую жизнь в выставку и расширить ее репертуар?

The next important stage in the history of the Biennale was to be Rem Koolhaas’s acceptance of the invitation to act as its curator. He decided to go back to basics with his “Fundamentals”, and did not include any of the stars of the discipline who had been permanent participants in the exhibition for many years. In 2014, therefore, these “starchitects” were replaced by the base elements of architecture: the floor, walls, a roof, doors, toilets, all subjected to meticulous research by the students of Harvard. “Now, in the age of digital technology, the main risk is that architecture will be incapable of thinking of its own arsenal”, – Koolhaas warned. However, it was unclear how the all-devouring flow of information might enable such conceptualisation, – all findings remaining in spite of everything on the level of intellectual balancing acts. The national pavilions, having diligently studied their own modernist heritage, likewise were left where they had started. The exhibition thus lasted six months rather than three.

In almost four decades, the Biennale had travelled the road from a semi-informal venue to a major aggregator of the architectural establishment. The selection of Alejandro Aravena to head the forthcoming 15th Architectural Biennale signifies yet another harking back to matters of ethics. Aravena is perhaps one of the most socially oriented curators in the history of the Biennale and one of the most striking representatives of the new generation. Will he succeed in breathing new life into the exhibition and widen its repertoire?